Venise Italie Vénétie vue des airs palais économies picturaux cathédrale canaux îles ÉNORME

Venise Italie Vénétie vue des airs palais économies picturaux cathédrale canaux îles ÉNORME, Venise Italie Vénétie vue des airs palais picturaux cathédrale canaux îles ÉNORME le moins cher

SKU: 490079

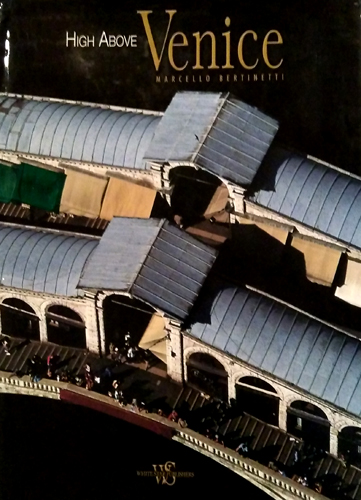

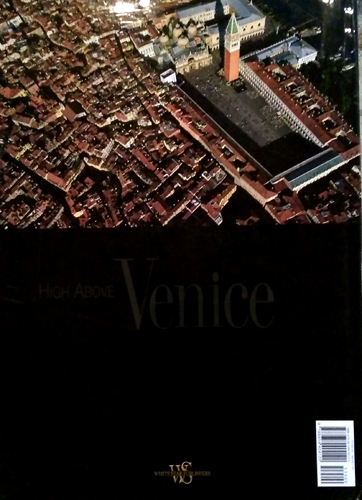

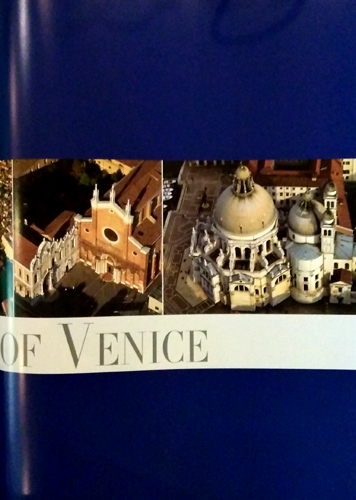

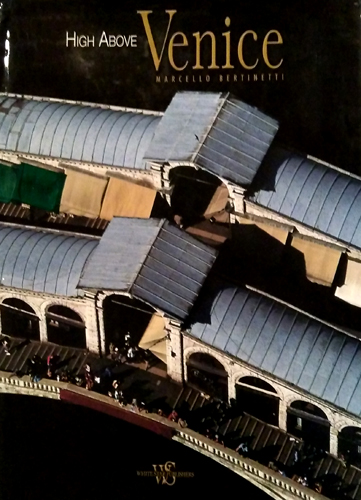

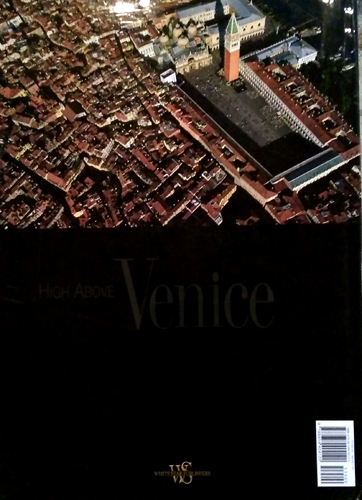

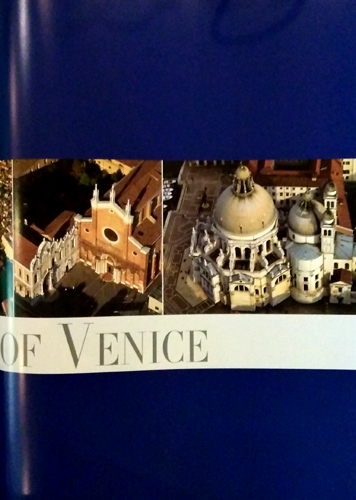

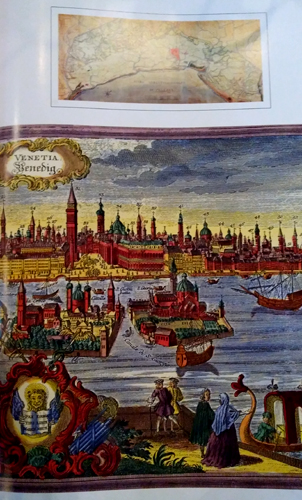

"High Above Venice" by Marcello Bertinetti.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

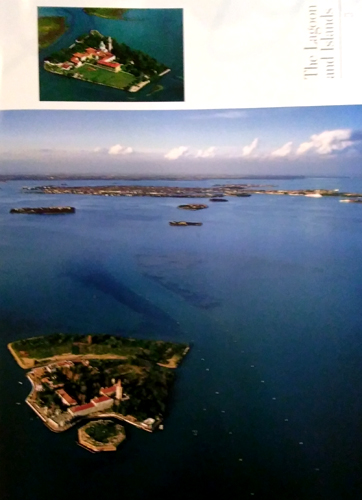

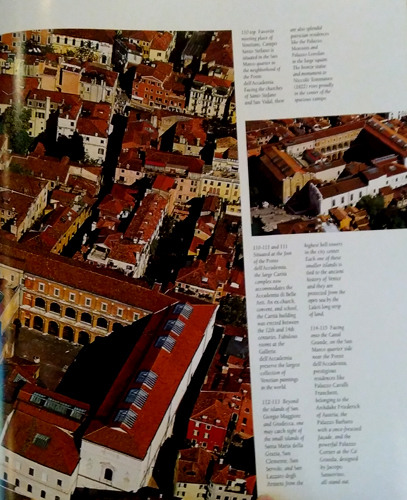

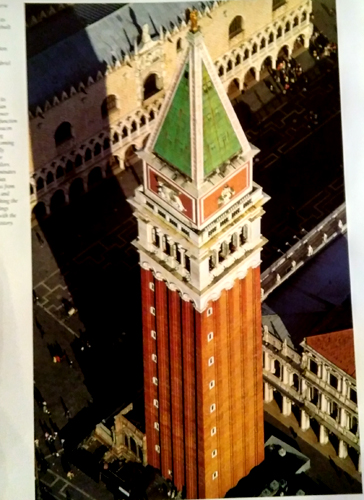

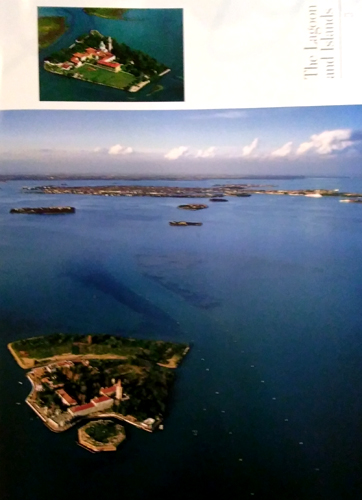

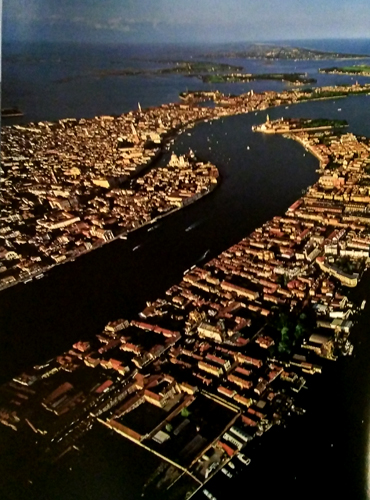

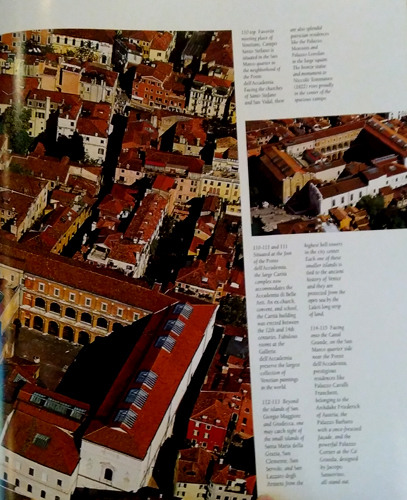

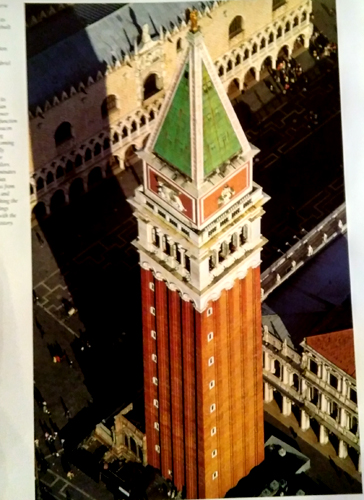

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with dustjacket. Publisher: White Star (2008). Pages: 192. Size: 16¾ x 12 x ¾ inch; 5½ pounds. Summary: Featuring hundreds of bird’s-eye photographs, this volume expands our perceptions of a city that already looms large in our mind’s eye. Whisking readers above Venice and its surrounding region, these images depict a city that is as breathtakingly beautiful in reality as it is in our imagination. A wide variety of panoramas depict the sights that are distinctly Venetian: the emerald-green Lagoon with its picturesque islands of Burano, Torcello, and Murano, the brightly-colored homes of Burano, the network of canals branching out from the S-shaped Grand Canal, the venerable palaces, centuries-old homes, and world-famous monuments which are all the more compelling when viewed from above. For anyone who has experienced the magic of Venice and the Veneto, this volume is a souvenir to be cherished. And for anyone who hopes to travel to this area, it will serve as an inspiration as well.

CONDITION: VERY GOOD. MASSIVE "new" (albeit shopworn) hardcover w/dustjacket. White Star (2008) 192 pages.Book looks like it was a display copy in an open-shelf bookstore. Its always possibleit was read, but if so, it was by someone with an extremely light hand. Evidencesuggests it is likely it was flipped through a few times while on display, but theresno evidence it was actually read through. However the book does evidence some lightbumping to the spine head and heel, as well as the open corners. If you scrutinize theinside of the book very intently, you might see very small, faint bend marks to theinside corner of the first and last dozen pages within the book. Super-sized, heavybooks like this are awkward to handle and so tend to get dragged across and bumped intobook shelves as they are shelved and re-shelved, so it is not uncommon to seeaccelerated edge and corner shelfwear to both the dustjacket and covers of such huge,heavy books). Inside, except for the (almost indiscernible) bump/bend marks to theinside corner of a few pages, the book is virtually pristine. The pages are pristine;clean, crisp, unmarked, (otherwise) unmutilated, tightly bound, and though likelyflipped through once or twice, seemingly otherwise unread. Outside the book evidencessome "shopwear". The dustjacket evidences very mild "crinkling" at the top open edges,the spine head and heel (moreso to the head than the heel), and the top "tips" (the topopen corners of the dustjacket, front and back). Beneath the dustjacket the full clothcovers are clean and unsoiled, and as with the dustjacket, evidence only mild edge andcorner shelfwear (particularly light bumping to the corners). Except for the mildcorner bumping, the overall condition of the book is not too far distant from whatmight otherwise pass a new oversized stock from a open-shelf bookstore environment(such as Barnes & Noble or B. Dalton, for example) wherein patrons are permitted tobrowse the open bookshelves and so otherwise "new" books might show minor signs ofshelfwear, browsing wear, or other minute superficial cosmetic blemishes, consequenceof simply being shelved and re-shelved. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. Instock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED,DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! #8782a.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Featuring hundreds of birds-eye photographs, this volume expands our perceptions of a city that already looms large in our minds eye. Taking readers on an aerial adventure above this ever-fascinating city and its surrounding, the images in "High Above Venice" depict a city that is as breathtakingly beautiful in reality as it is in our imagination. A wide variety of panoramas depict the sights that are distinctly Venetian: the emerald-green Lagoon with its picturesque islands of Burano, Torcello, and Murano, the brightly-colored homes of Burano, the network of canals branching out from the S shaped Grand Canal, the venerable palaces, centuries-old homes, and world-famous monuments which are all the more compelling when viewed from above. For anyone who has experienced the magic of Venice, this volume is a souvenir to be cherished. And for anyone who hopes to travel to this city, it will serve as inspiration.

REVIEW: Acclaimed photographer Marcello Bertinetti has been published in many major magazines and periodicals. In addition, his work has been published in numerous books and used in major advertising campaigns. In 1984, he founded White Star Publishing. He currently works as publisher of the company as well as continuing to work as a professional photographer.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

TABLE OF CONTENTS: Introduction.

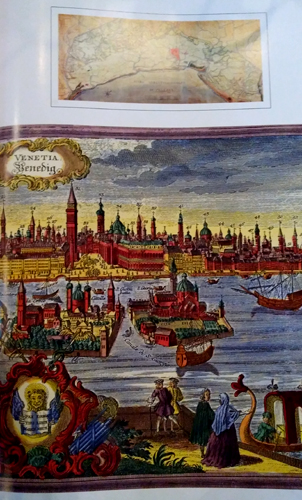

History.

San Marco.

The Heart of Venice.

Venice the Great.

The Lagoon and Islands

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: This volume takes readers on an aerial adventure above this ever-fascinating city and its surrounding region. A wide variety of panoramas depict the sights that are unique to Venice: the Lagoon with its islands of Burano, Torcello, and Murano; the network of canals branching out from the Grand Canal; the palaces, homes, and world-famous monuments that are all the more compelling when viewed from above. Chapters devoted to the Veneto region take readers to the neighboring cities of Vicenza, Padua, and Treviso as well as more obscure areas where photographs showcase lovely villages and castles, such as Citadel, Asolo, Bassano, and Chioggia. For anyone who wants to experience the magic of Venice and the Veneto, this volume is a souvenir to be cherished.

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: This is a truly superb book. It is huge and glossy and full of the most gorgeous photographs. If you are a fellow addict of La Serenissima this will bring back many happy memories of trips past, and jolt some you had forgotten back to your memory. If you havent been yet it will whet your appetite. It will also make you realize just how far you actually walk when you are there! Leave it somewhere where you will flip through it often, it will help feed your addiction until your next fix of this enchanting city. I love it and it was a wonderful addition to my Venetian library.

REVIEW: This book is fabulous! The pictures are worth 1,000 words. Highly recommend this book.

REVIEW: This book is fabulous! The pictures are worth 1,000 words. Highly recommend this book.REVIEW: Five stars! Incredible photography!

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

The Renaissance Culture: The Renaissance was a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to Modernity, roughly covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It occurred after the “Crisis of the Late Middle Ages” and was associated with great social change. Proponents of a long Renaissance put its beginning in the 14th century and its end in the 17th century. The traditional view focuses more on the early modern aspects of the Renaissance and argues that it was a break from the past. However many historians today focus more on its medieval aspects and argue that it was an extension of the Middle Ages.

The intellectual basis of the Renaissance was its version of humanism. This was derived from the concept of Roman Humanitas, and the rediscovery of classical Greek philosophy. An example might be such as that of Protagoras, the 5th century B.C. Greek Philosopher, who said that "…man is the measure of all things..." This new thinking became manifest in art, architecture, politics, science and literature. Early examples were the development of perspective in oil painting and the recycled knowledge of how to make concrete. Although the invention of metal movable type sped the dissemination of ideas from the later 15th century, the changes of the Renaissance were not uniformly experienced across Europe.

The first traces of the Renaissance appear in Italy as early as the late 13th century, in particular with the writings of Dante and the paintings of Giotto. As a cultural movement the Renaissance encompassed innovative flowering of Latin and vernacular literatures. This began with the 14th century resurgence of learning based on classical sources, which contemporaries credited to Petrarch. Additionally there was the development of linear perspective and other techniques of rendering a more natural reality in painting. No less significant was gradual but widespread educational reform.

The first traces of the Renaissance appear in Italy as early as the late 13th century, in particular with the writings of Dante and the paintings of Giotto. As a cultural movement the Renaissance encompassed innovative flowering of Latin and vernacular literatures. This began with the 14th century resurgence of learning based on classical sources, which contemporaries credited to Petrarch. Additionally there was the development of linear perspective and other techniques of rendering a more natural reality in painting. No less significant was gradual but widespread educational reform.In politics the Renaissance contributed to the development of the customs and conventions of diplomacy. In science the Renaissance led to an increased reliance on observation and inductive reasoning. The Renaissance saw revolutions in many intellectual pursuits, as well as social and political upheaval. However it is perhaps best known for its artistic developments and the contributions of such polymaths as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who inspired the term "Renaissance Man".

Historians attribute the beginning of the Renaissance to 14th century Florence, Italy. Various theories have been proposed to account for its origins and characteristics. Theories generally focus on a variety of factorsincluding the social and civic peculiarities of Florence at the time. These include its political structure and the patronage of its dominant family, the Medici. Another potentially significant factor was the migration of Greek scholars and their texts to Italy following the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks.

Other major centers of the Renaissance were northern Italian city-states such as Venice, Genoa, Milan, Bologna, and Rome during the Renaissance Papacy. Also were Belgian cities such as Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, Leuven or Antwerp. The Renaissance has a long and complex historiography. In line with general skepticism of discrete periodizations there has been much debate among historians. In particular historians question the 19th-century glorification of the "Renaissance" and individual culture heroes as "Renaissance Men". In general historians question the usefulness of Renaissance as a term and as a historical delineation.

Other major centers of the Renaissance were northern Italian city-states such as Venice, Genoa, Milan, Bologna, and Rome during the Renaissance Papacy. Also were Belgian cities such as Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, Leuven or Antwerp. The Renaissance has a long and complex historiography. In line with general skepticism of discrete periodizations there has been much debate among historians. In particular historians question the 19th-century glorification of the "Renaissance" and individual culture heroes as "Renaissance Men". In general historians question the usefulness of Renaissance as a term and as a historical delineation.The art historian Erwin Panofsky observed of this resistance to the concept of the "Renaissance", “…it is perhaps no accident that the factuality of the Italian Renaissance has been most vigorously questioned by those who are not obliged to take a professional interest in the aesthetic aspects of civilization – historians of economic and social developments, political and religious situations, and, most particularly, natural science – but only exceptionally by students of literature and hardly ever by historians of Art…” Some observers have called into question whether the Renaissance was a cultural "advance" from the Middle Ages. Instead they view it as a period of pessimism and nostalgia for classical antiquity. Social and economic historians have focused on the continuity between the Middle ages and the Renaissance, which they argue are linked "by a thousand ties".

The term rinascita (“rebirth”) first appeared in Giorgio Vasaris “Lives of the Artists”, written about 1550AD. The term “rinascita” was anglicized as the “Renaissance” in the 1830s. The word has also been extended to other historical and cultural movements, such as the Carolingian Renaissance (of the 8th and 9th centuries), the Ottonian Renaissance (of the 10th and 11th centuries), the Timurid Renaissance (Islamic Central Asia late 14th through early 17th centuries), and the Renaissance of the 12th century. More than anything the Renaissance was a cultural movement that profoundly affected European intellectual life in the early modern period.

The term rinascita (“rebirth”) first appeared in Giorgio Vasaris “Lives of the Artists”, written about 1550AD. The term “rinascita” was anglicized as the “Renaissance” in the 1830s. The word has also been extended to other historical and cultural movements, such as the Carolingian Renaissance (of the 8th and 9th centuries), the Ottonian Renaissance (of the 10th and 11th centuries), the Timurid Renaissance (Islamic Central Asia late 14th through early 17th centuries), and the Renaissance of the 12th century. More than anything the Renaissance was a cultural movement that profoundly affected European intellectual life in the early modern period.After its beginnings in Italy it spread to the rest of Europe by the 16th century. Its influence was felt in art, architecture, philosophy, literature, music, science and technology, politics, religion, and other aspects of intellectual inquiry. Renaissance scholars employed the humanist method in study, and searched for realism and human emotion in art. Renaissance humanists sought out in Europes monastic libraries the Latin literary, historical, and oratorical texts of Antiquity. The Fall of Constantinople in 1453 generated a wave of émigré Greek scholars bringing precious manuscripts in ancient Greek, Many of these manuscripts had fallen into obscurity in the West. It is in their new focus on literary and historical texts that Renaissance scholars differed so markedly from the medieval scholars of the Renaissance of the 12th century. Those scholars of the 12th century had focused on studying Greek and Arabic works of natural sciences, philosophy and mathematics, rather than on such classical cultural texts.

In the revival of neo-Platonism Renaissance humanists did not reject Christianity. Quite to the contrary many of the greatest works of the Renaissance were devoted to Christianity. The Church in turn patronized many works of Renaissance art. However a subtle shift took place in the way that intellectuals approached religion. This shift in perspective was reflected in many other areas of cultural life. In addition many Greek Christian works were brought back from Byzantium to Western Europe. These included the Greek New Testament. These Greek Christian works engaged Western scholars for the first time since late antiquity. This new engagement and in particular the return to the original Greek of the New Testament promoted by humanists would help pave the way for the Protestant Reformation.

In the revival of neo-Platonism Renaissance humanists did not reject Christianity. Quite to the contrary many of the greatest works of the Renaissance were devoted to Christianity. The Church in turn patronized many works of Renaissance art. However a subtle shift took place in the way that intellectuals approached religion. This shift in perspective was reflected in many other areas of cultural life. In addition many Greek Christian works were brought back from Byzantium to Western Europe. These included the Greek New Testament. These Greek Christian works engaged Western scholars for the first time since late antiquity. This new engagement and in particular the return to the original Greek of the New Testament promoted by humanists would help pave the way for the Protestant Reformation.Well after the first artistic return to classicism had been exemplified in the sculpture of Nicola Pisano, Florentine painters led by Masaccio strove to portray the human form realistically. This entailed developing techniques to render perspective and light more naturally. Political philosophers sought to describe political life as it really was, that is to understand it rationally. One more prominent example was most famously Niccolò Machiavelli. A critical contribution to Italian Renaissance humanism was made by Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. He wrote in 1486 the famous text “De hominis dignitate”, or “Oration on the Dignity of Man”. This consisted of a series of literary works on philosophy, and natural thought. He defended faith and magic against any opponent on the grounds of reason.

In addition to studying classical Latin and Greek, Renaissance authors also began increasingly to use vernacular languages. This combined with the introduction of printing press would allow many more people access to books, especially the Bible. Overall the Renaissance could be viewed as an attempt by intellectuals to study and improve the secular and worldly. This they strived to effect both through the revival of ideas from antiquity, and through novel approaches to thought. Some contemporary scholars play down the significance of the Renaissance. They rather believe that the earlier innovations of the Italian city-states in the High Middle Ages were more significant. These innovations had married responsive government, Christianity and the birth of capitalism.

In addition to studying classical Latin and Greek, Renaissance authors also began increasingly to use vernacular languages. This combined with the introduction of printing press would allow many more people access to books, especially the Bible. Overall the Renaissance could be viewed as an attempt by intellectuals to study and improve the secular and worldly. This they strived to effect both through the revival of ideas from antiquity, and through novel approaches to thought. Some contemporary scholars play down the significance of the Renaissance. They rather believe that the earlier innovations of the Italian city-states in the High Middle Ages were more significant. These innovations had married responsive government, Christianity and the birth of capitalism. This perspective argues that the great European states (i.e., France and Spain) were absolutist monarchies. Other European states were under direct Church control. In contrast the independent city republics of the Italian High Middle Ages took over the principles of capitalism invented on monastic estates. In so doing they set off a vast unprecedented commercial revolution that preceded and financed the Renaissance. Many contemporary historians argue that the ideas characterizing the Renaissance had their origin in late 13th century Florence, Italy. In particular they point to the writings of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) and Petrarch (1304–1374); as well as the paintings of Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337).

Some writers date the Renaissance quite precisely. One proposed starting point is 1401 AD. This was the year when the rival geniuses Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi competed for the contract to build the bronze doors for the Baptistery of the Florence Cathedral (Ghiberti won). Other historians see more general competition between artists and polymaths such as Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello, and Masaccio. They argue that these competitions for artistic commissions sparked the creativity of the Renaissance. Yet it remains much debated why the Renaissance began in Italy, and why it began when it did.

Accordingly several theories have been put forward to explain the origins of the Renaissance. During the Renaissance money and art went hand in hand. Artists depended entirely on patrons while the patrons needed money to foster artistic talent. Wealth was brought to Italy in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries by expanding trade into Asia and Europe. Silver mining in Tyrol (the Northern Italian Alps) increased the flow of money. Luxuries brought home from the Muslim world during the Crusades increased the prosperity of Genoa and Venice. Many contemporary historians define the 16th century Renaissance in France as a period in Europes cultural history that represented a break from the Middle Ages. They posit that this period in France created a modern understanding of humanity and its place in the world.

Accordingly several theories have been put forward to explain the origins of the Renaissance. During the Renaissance money and art went hand in hand. Artists depended entirely on patrons while the patrons needed money to foster artistic talent. Wealth was brought to Italy in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries by expanding trade into Asia and Europe. Silver mining in Tyrol (the Northern Italian Alps) increased the flow of money. Luxuries brought home from the Muslim world during the Crusades increased the prosperity of Genoa and Venice. Many contemporary historians define the 16th century Renaissance in France as a period in Europes cultural history that represented a break from the Middle Ages. They posit that this period in France created a modern understanding of humanity and its place in the world.During the High Middle Ages Latin scholars focused almost entirely on studying Greek and Arabic works of natural science, philosophy and mathematics. In dramatic contrast Renaissance scholars were most interested in recovering and studying Latin and Greek literary, historical, and oratorical texts. Broadly speaking this began in the 14th century with a Latin phase. It started with Renaissance scholars such as Petrarch, Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), Niccolò de Niccoli (1364–1437) and Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459) scouring the libraries of Europe. They were searching for works by such Latin authors as Cicero, Lucretius, Livy and Seneca.

By the early 15th century the bulk of the surviving such Latin literature had been recovered. Western European scholars turned to recovering ancient Greek literary, historical, oratorical and theological texts. The Greek phase of Renaissance humanism was under way. Latin texts had been preserved and studied in Western Europe since late antiquity. In contrast the study of ancient Greek texts was very limited in medieval Western Europe. Ancient Greek works on science, math and philosophy had been studied since the High Middle Ages in Western Europe. In translation it has also been extensively studied in the Islamic Golden Age.

However this was not the case with Greek literary, oratorical and historical works. Homer, the Greek dramatists, Demosthenes and Thucydides) were not studied in either the Latin or medieval Islamic worlds. In the Middle Ages these sorts of texts were only studied by Byzantine scholars. Some historians argue that the Timurid Renaissance in Samarkand was linked with Ottoman Empire. They posit that those conquests resulted in the mass migration of Greek scholars to Italian cities. One of the greatest achievements of Renaissance scholars was to bring this entire class of Greek cultural works back into Western Europe for the first time since late antiquity.

However this was not the case with Greek literary, oratorical and historical works. Homer, the Greek dramatists, Demosthenes and Thucydides) were not studied in either the Latin or medieval Islamic worlds. In the Middle Ages these sorts of texts were only studied by Byzantine scholars. Some historians argue that the Timurid Renaissance in Samarkand was linked with Ottoman Empire. They posit that those conquests resulted in the mass migration of Greek scholars to Italian cities. One of the greatest achievements of Renaissance scholars was to bring this entire class of Greek cultural works back into Western Europe for the first time since late antiquity.Muslim scholars had inherited Greek ideas after they had invaded and conquered Egypt and the Levant. Their translations and commentaries on these ideas worked their way through the Arab West into Iberia and Sicily. These areas became important centers for this transmission of ideas. From the 11th to the 13th centuries many schools dedicated to the translation of philosophical and scientific works from Classical Arabic to Medieval Latin were established in Iberia. Most notably the Toledo School of Translators. Though largely unplanned and disorganized this work of translation from Islamic culture constituted one of the greatest transmissions of ideas in history.

There commenced a movement to reintegrate the regular study of Greek literary, historical, oratorical and theological texts back into the Western European curriculum. This is usually dated to the 1396 invitation from Coluccio Salutati to the Byzantine diplomat and scholar Manuel Chrysoloras to teach Greek in Florence. This legacy was continued by a number of expatriate Greek scholars, from Basilios Bessarion to Leo Allatius. The unique political structures of late Middle Ages Italy have led some historians to theorize that its unusual social climate allowed the emergence of a rare cultural efflorescence. Italy did not exist as a political entity in the early modern period. It was divided into smaller city states and territories. The Kingdom of Naples controlled the south. The Republic of Florence and the Papal States governed central Italy. The Milanese governed the North. The Genoese governed the west. The Venetians controlled the Italian east.

There commenced a movement to reintegrate the regular study of Greek literary, historical, oratorical and theological texts back into the Western European curriculum. This is usually dated to the 1396 invitation from Coluccio Salutati to the Byzantine diplomat and scholar Manuel Chrysoloras to teach Greek in Florence. This legacy was continued by a number of expatriate Greek scholars, from Basilios Bessarion to Leo Allatius. The unique political structures of late Middle Ages Italy have led some historians to theorize that its unusual social climate allowed the emergence of a rare cultural efflorescence. Italy did not exist as a political entity in the early modern period. It was divided into smaller city states and territories. The Kingdom of Naples controlled the south. The Republic of Florence and the Papal States governed central Italy. The Milanese governed the North. The Genoese governed the west. The Venetians controlled the Italian east. Despite the political fragmentation 15th century Italy was one of the most urbanized regions in Europe. Many of its cities stood among the ruins of ancient Roman buildings. It seems likely that the classical nature of the Renaissance was linked to its origin in the Roman Empires former heartland. A German bishop visiting north Italy during the 12th century noticed a widespread new form of political and social organization. He observed that Italy appeared to have exited from Feudalism so that its society was based on merchants and commerce. Linked to this was anti-monarchical thinking. This was perhaps best represented in the famous early Renaissance fresco cycle painted from 1338-1340 “The Allegory of Good and Bad Government” by Ambrogio Lorenzetti.

The strong message it conveyed pertained to the virtues of fairness, justice, republicanism and good administration. In defiance of norms of both Church and Empire, these city republics were devoted to notions of liberty. There were many demonstrations in the defense of liberty such as the celebration of Florentine genius. These were not restricted merely to art, sculpture and architecture. Rather they extended to the remarkable efflorescence of moral, social and political philosophy that occurred in Florence at the same time. Even cities and states beyond central Italy were also notable for their merchant Republics. This included not only Florence, but in particular the Republic of Venice.

The strong message it conveyed pertained to the virtues of fairness, justice, republicanism and good administration. In defiance of norms of both Church and Empire, these city republics were devoted to notions of liberty. There were many demonstrations in the defense of liberty such as the celebration of Florentine genius. These were not restricted merely to art, sculpture and architecture. Rather they extended to the remarkable efflorescence of moral, social and political philosophy that occurred in Florence at the same time. Even cities and states beyond central Italy were also notable for their merchant Republics. This included not only Florence, but in particular the Republic of Venice. In practice of course these political entities were oligarchical. They bore little resemblance to a modern democracy. However they did possess democratic features and were responsive states. They featured both forms of participation in governance and belief in liberty. The relative political freedom they afforded was conducive to academic and artistic advancement. Likewise the influence and prominence of Italian cities such as Venice as great trading centers made them intellectual crossroads. Merchants brought with them ideas from far corners of the globe, particularly the Levant. Venice was Europes gateway to trade with the East. Venice was also a dominant producer of fine glass, while Florence was a capital of textiles. The wealth such business brought to Italy not only meant large public and private artistic projects could be commissioned. It also meant that individuals had more leisure time for study.

Pieter Bruegels oil painting “The Triumph of Death” (finished about 1562) reflects the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague that devastated medieval Europe between 1348 and 1350. Historians theorize that the devastation in Florence caused by the Black Death resulted in a shift in the world view ofpeople in 14th century Italy. Italy was particularly badly hit by the plague. It has been postulated that the resulting familiarity with death caused thinkers to dwell more on their lives on Earth, rather than on spirituality and the afterlife. Conversely it has also been argued that the Black Death prompted a new wave of piety. This allegedly manifested itself in the sponsorship of religious works of art.

Pieter Bruegels oil painting “The Triumph of Death” (finished about 1562) reflects the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague that devastated medieval Europe between 1348 and 1350. Historians theorize that the devastation in Florence caused by the Black Death resulted in a shift in the world view ofpeople in 14th century Italy. Italy was particularly badly hit by the plague. It has been postulated that the resulting familiarity with death caused thinkers to dwell more on their lives on Earth, rather than on spirituality and the afterlife. Conversely it has also been argued that the Black Death prompted a new wave of piety. This allegedly manifested itself in the sponsorship of religious works of art.However this does not fully explain why the Renaissance occurred specifically in Italy in the 14th century. The Renaissances emergence in Italy was most likely the result of the complex interaction of all of the factors discussed above. After all the Black Death was a pandemic that affected all of Europe in the ways described, not only Italy. The plague was carried by fleas on sailing vessels returning from the ports of Asia. It spread quickly due to lack of proper sanitation. England with a total population of about 4.2 million, lost 1.4 million people to the bubonic plague. Florences population was nearly halved in the year 1347.

As a result of the severe depopulation the value of the labors performed by the working class increased. Commoners came to enjoy more freedom as well as increased incomes. To answer the increased need for labor, workers traveled in search of the most economically advantageous markets. The demographic decline due to the plague had multiple economic consequences. The prices of food dropped and land values declined by 30 to 40% in most parts of Europe between 1350 and 1400. Landholders faced a great loss. However for ordinary men and women it was a windfall. The survivors of the plague found not only that the prices of food were cheaper but also that lands were more abundant. Many landless commoners found that they had inherited property from their dead relations.

As a result of the severe depopulation the value of the labors performed by the working class increased. Commoners came to enjoy more freedom as well as increased incomes. To answer the increased need for labor, workers traveled in search of the most economically advantageous markets. The demographic decline due to the plague had multiple economic consequences. The prices of food dropped and land values declined by 30 to 40% in most parts of Europe between 1350 and 1400. Landholders faced a great loss. However for ordinary men and women it was a windfall. The survivors of the plague found not only that the prices of food were cheaper but also that lands were more abundant. Many landless commoners found that they had inherited property from their dead relations.The spread of disease was significantly more rampant in areas of poverty and in urban areas. Epidemics ravaged cities, particularly children. Plagues were easily spread by fleas, unsanitary drinking water, armies, or by poor sanitation. Children were hit the hardest because many widespread diseases such as typhus and syphilis target the immune system. With compromised immune systems, many young children were left without a fighting chance. Children in city dwellings were more affected by the spread of disease than the children of the wealthy.

The Black Death caused greater upheaval to Florences social and political structure than later epidemics. Despite a significant number of deaths among members of the ruling classes, the government of Florence continued to function during this period. Formal meetings of elected representatives were suspended during the height of the epidemic due to the chaotic conditions in the city. However a small group of officials was appointed to conduct the affairs of the city. These officials ensured continuity of government.

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in Florence, and not elsewhere in Italy. Scholars have noted several features unique to Florentine cultural life that may have caused such a cultural movement. Many have emphasized the role played by the Medici. The Medici were a banking family and later ducal ruling house, playing a significant role in patronizing and stimulating the arts. Lorenzo de Medici who lived from 1449 to 1492 was the catalyst for an enormous amount of arts patronage. In addition to his own patronage he encouraged his countrymen to commission works from the leading artists of Florence. They patronized such notables as included Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo Buonarroti. Additional works by Neri di Bicci, Botticelli, da Vinci and Filippino Lippi were also commissioned additionally by the Convent of San Donato in Scopeto in Florence.

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in Florence, and not elsewhere in Italy. Scholars have noted several features unique to Florentine cultural life that may have caused such a cultural movement. Many have emphasized the role played by the Medici. The Medici were a banking family and later ducal ruling house, playing a significant role in patronizing and stimulating the arts. Lorenzo de Medici who lived from 1449 to 1492 was the catalyst for an enormous amount of arts patronage. In addition to his own patronage he encouraged his countrymen to commission works from the leading artists of Florence. They patronized such notables as included Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo Buonarroti. Additional works by Neri di Bicci, Botticelli, da Vinci and Filippino Lippi were also commissioned additionally by the Convent of San Donato in Scopeto in Florence.The Renaissance had already certainly been under way before Lorenzo de Medici came to power. Indeed the Renaissance was emergent even before the Medici family itself achieved hegemony in Florentine society. Some historians have postulated that Florence was the birthplace of the Renaissance as a result of luck. They assert that "Great Men" were born there by simply by chance. Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli and Michelangelo were all born in Tuscany. Arguing that such chance seems improbable, other historians have contended that these "Great Men" were only able to rise to prominence because of the prevailing cultural conditions at the time.

In some ways Renaissance humanism was not a philosophy but a method of learning. The medieval scholastic mode focused on resolving contradictions between authors of Latin classics. In contrast Renaissance humanists would study ancient texts in the original and appraise them through a combination of reasoning and empirical evidence. Humanist education was based on the program of “Studia Humanitatis”. This embraced the study of five humanities: poetry, grammar, history, moral philosophy and rhetoric. Historians have sometimes struggled to define humanism precisely. However a widely acceptable “middle of the road definition” has been the movement to recover, interpret, and assimilate the language, literature, learning and values of ancient Greece and Rome. Above all, humanists asserted "the genius of man” and the “unique and extraordinary ability of the human mind".

In some ways Renaissance humanism was not a philosophy but a method of learning. The medieval scholastic mode focused on resolving contradictions between authors of Latin classics. In contrast Renaissance humanists would study ancient texts in the original and appraise them through a combination of reasoning and empirical evidence. Humanist education was based on the program of “Studia Humanitatis”. This embraced the study of five humanities: poetry, grammar, history, moral philosophy and rhetoric. Historians have sometimes struggled to define humanism precisely. However a widely acceptable “middle of the road definition” has been the movement to recover, interpret, and assimilate the language, literature, learning and values of ancient Greece and Rome. Above all, humanists asserted "the genius of man” and the “unique and extraordinary ability of the human mind". Humanist scholars shaped the intellectual landscape throughout the early modern period. Political philosophers such as Niccolò Machiavelli and Thomas More revived the ideas of Greek and Roman thinkers and applied them in critiques of contemporary government. Pico della Mirandola wrote a vibrant defense of thinking which is regarded as the "manifesto" of the Renaissance, the “Oration on the Dignity of Man”. Another humanist Matteo Palmieri is most known for his work Della vita civile ("On Civic Life"). Printed in 1528 it advocated civic humanism. Notably it was printed in a refined Tuscan vernacular every bit the equivalent in sophisticated as Latin. Palmieri drew on Roman philosophers and theorists, especially Cicero. Like Palmieri Cicero had lived an active public life as a citizen and official, as well as a theorist and philosopher, and Quintilian.

Perhaps the most succinct expression of Palmieri’s perspective on humanism is in a 1465 poetic work “La città di vita”. However an earlier work “Della vita civile” was more wide-ranging. It was composed as a series of dialogues set in a country house in the Mugello countryside outside Florence during the plague of 1430. Within it Palmieri expounds on the qualities of the ideal citizen. The dialogues include ideas about how children develop mentally and physically. Also include are ideas on how citizens can conduct themselves morally. Further ideas are included pertaining to how citizens and states can ensure probity in public life. And also included is an important debate on the difference between that which is pragmatically useful and that which is honest.

Perhaps the most succinct expression of Palmieri’s perspective on humanism is in a 1465 poetic work “La città di vita”. However an earlier work “Della vita civile” was more wide-ranging. It was composed as a series of dialogues set in a country house in the Mugello countryside outside Florence during the plague of 1430. Within it Palmieri expounds on the qualities of the ideal citizen. The dialogues include ideas about how children develop mentally and physically. Also include are ideas on how citizens can conduct themselves morally. Further ideas are included pertaining to how citizens and states can ensure probity in public life. And also included is an important debate on the difference between that which is pragmatically useful and that which is honest.The humanists believed that it is important to transcend to the afterlife with a perfect mind and body, which could be attained with education. The purpose of humanism was to create a universal man whose person combined intellectual and physical excellence. To create the ideal of a man who was capable of functioning honorably in virtually any situation. This ideology was referred to as the “uomo universale”, an ancient Greco-Roman ideal. Education during the Renaissance was mainly composed of ancient literature and history. It was believed that the classics provided moral instruction and an intensive understanding of human behavior.

A unique characteristic of some Renaissance libraries was that they were open to the public. These libraries were places where ideas were exchanged and where scholarship and reading were considered both pleasurable and beneficial to the mind and soul. As freethinking was a hallmark of the age, many libraries contained a wide range of writers. Classical texts could be found alongside humanist writings. These informal associations of intellectuals profoundly influenced Renaissance culture. Some of the richest "bibliophiles" built libraries as temples to books and knowledge. A number of libraries appeared as manifestations of immense wealth joined with a love of books. In some cases, cultivated library builders were also committed to offering others the opportunity to use their collections. Prominent aristocrats and princes of the Church created great libraries for the use of their courts. Called "court libraries" they were housed in lavishly designed monumental buildings decorated with ornate woodwork, and the walls adorned with frescoes.

A unique characteristic of some Renaissance libraries was that they were open to the public. These libraries were places where ideas were exchanged and where scholarship and reading were considered both pleasurable and beneficial to the mind and soul. As freethinking was a hallmark of the age, many libraries contained a wide range of writers. Classical texts could be found alongside humanist writings. These informal associations of intellectuals profoundly influenced Renaissance culture. Some of the richest "bibliophiles" built libraries as temples to books and knowledge. A number of libraries appeared as manifestations of immense wealth joined with a love of books. In some cases, cultivated library builders were also committed to offering others the opportunity to use their collections. Prominent aristocrats and princes of the Church created great libraries for the use of their courts. Called "court libraries" they were housed in lavishly designed monumental buildings decorated with ornate woodwork, and the walls adorned with frescoes.Renaissance art marks a cultural rebirth at the close of the Middle Ages and rise of the modern world. One of the distinguishing features of Renaissance art was its development of highly realistic linear perspective. Giotto di Bondone (who lived from 1267 to 1337) is credited with first treating a painting as a window into space. However but it was not until the demonstrations of architect Filippo Brunelleschi (who lived from to 1446) and the subsequent writings of Leon Battista Alberti (who lived from 1404 to 1472) that perspective was formalized as an artistic technique. Leonardo da Vincis Vitruvian Man (about 1490) demonstrates the effect writers of antiquity had on Renaissance thinkers. Based on the specifications in Vitruvius “De architectura” Leonardo tried to draw the perfectly proportioned man. Vitruvius was a Roman Engineer and Architect. He wrote “De architectura” or “On Architecture” was written in the 1st century BC).

The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts. Painters developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of Leonardo da Vinci, human anatomy. Underlying these changes in artistic method was a renewed desire to depict the beauty of nature and to unravel the axioms of aesthetics. The works of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael represented artistic pinnacles that were much imitated by other artists. Other notable artists of the era included Sandro Botticelli, working for the Medici in Florence. Also Donatello, another Florentine, and Titian in Venice, amongst many others.

The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts. Painters developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of Leonardo da Vinci, human anatomy. Underlying these changes in artistic method was a renewed desire to depict the beauty of nature and to unravel the axioms of aesthetics. The works of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael represented artistic pinnacles that were much imitated by other artists. Other notable artists of the era included Sandro Botticelli, working for the Medici in Florence. Also Donatello, another Florentine, and Titian in Venice, amongst many others.In the Netherlands a particularly vibrant artistic culture developed. The work of Hugo van der Goes and Jan van Eyck was particularly influential on the development of painting in Italy. The influence was both technical with the introduction of oil paint and canvas, and stylistic in terms of naturalism in representation. Later the work of Pieter Brueghel the Elder would inspire artists to depict themes of everyday life. In architecture Filippo Brunelleschi was foremost in studying the remains of ancient classical buildings. Brunelleschi formulated the Renaissance style that emulated and improved on classical forms. He was aided and inspired by rediscovered knowledge from the 1st century writer Vitruvius and the flourishing discipline of mathematics. His major feat of engineering was building the dome of the Florence Cathedral.

Another building demonstrating this style is the church of St. Andrew in Mantua, built by Alberti. The outstanding architectural work of the High Renaissance was the rebuilding of St. Peters Basilica. This combined the skills of Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Sangallo and Maderno. During the Renaissance architects aimed to use columns, pilasters, and entablatures as an integrated system. The Roman orders types of columns are used: Tuscan and Composite. These can either be structural, supporting an arcade or architrave, or purely decorative, set against a wall in the form of pilasters. One of the first buildings to use pilasters as an integrated system was in the Old Sacristy built between 1421 and 1440 by Brunelleschi.

Another building demonstrating this style is the church of St. Andrew in Mantua, built by Alberti. The outstanding architectural work of the High Renaissance was the rebuilding of St. Peters Basilica. This combined the skills of Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Sangallo and Maderno. During the Renaissance architects aimed to use columns, pilasters, and entablatures as an integrated system. The Roman orders types of columns are used: Tuscan and Composite. These can either be structural, supporting an arcade or architrave, or purely decorative, set against a wall in the form of pilasters. One of the first buildings to use pilasters as an integrated system was in the Old Sacristy built between 1421 and 1440 by Brunelleschi.Arches, semi-circular or (in the Mannerist style) segmental, were often used in arcades. They were supported on piers or columns with capitals. There may be a section of entablature between the capital and the springing of the arch. Alberti was one of the first to use the arch on a monumental. Renaissance vaults did not have ribs; they were semi-circular or segmental and on a square plan. This was unlike the Gothic vault, which was frequently rectangular. Renaissance artists were not pagans, although they admired antiquity and kept some ideas and symbols of the medieval past. Nicola Pisano who lived from about 1220 to 1278 imitated classical forms by portraying scenes from the Bible. His Annunciation, from the Baptistry at Pisa, demonstrates that classical models influenced Italian art before the Renaissance took root as a literary movement.

Applied innovation extended to Renaissance commerce as well. At the end of the 15th century Luca Pacioli published the first work on bookkeeping, making him the founder of accounting. The rediscovery of ancient texts and the invention of the printing press democratized learning. It also allowed for faster propagation of more widely distributed literary ideas. In the first period of the Italian Renaissance, humanists favored the study of humanities over natural philosophy or applied mathematics. Their reverence for classical sources further enshrined the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic views of the universe. Writing around 1450 Nicholas Cusanus anticipated the heliocentric worldview of Copernicus, but in a philosophical fashion.

Applied innovation extended to Renaissance commerce as well. At the end of the 15th century Luca Pacioli published the first work on bookkeeping, making him the founder of accounting. The rediscovery of ancient texts and the invention of the printing press democratized learning. It also allowed for faster propagation of more widely distributed literary ideas. In the first period of the Italian Renaissance, humanists favored the study of humanities over natural philosophy or applied mathematics. Their reverence for classical sources further enshrined the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic views of the universe. Writing around 1450 Nicholas Cusanus anticipated the heliocentric worldview of Copernicus, but in a philosophical fashion.Science and art were intermingled in the early Renaissance, with polymath artists such as Leonardo da Vinci making observational drawings of anatomy and nature. Da Vinci set up controlled experiments in water flow, medical dissection, and systematic study of movement and aerodynamics. He devised principles of research method that led Fritjof Capra to classify him as the "father of modern science". Other examples of Da Vincis contribution during this period include machines designed to saw marbles and lift monoliths. New discoveries in acoustics, botany, geology, anatomy, and mechanics are also attributed to Da Vinci. A suitable environment had developed to question scientific doctrine.

The discovery in 1492 of the New World by Christopher Columbus challenged the classical worldview. The works of the 2nd century Greco-Roman geographer “Geographia and the Cosmographia” Claudius Ptolemy it became clear were not always correct. Likewise the works of the 2nd century Roman physician, surgeon, and philosopher Galen of Pergamon in medicine were found to not always match everyday observations. As the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation clashed the Northern Renaissance showed a decisive shift in focus away from Aristotelean natural philosophy to chemistry and the biological sciences (botany, anatomy, and medicine). The willingness to question previously held truths and search for new answers resulted in a period of major scientific advancements.

The discovery in 1492 of the New World by Christopher Columbus challenged the classical worldview. The works of the 2nd century Greco-Roman geographer “Geographia and the Cosmographia” Claudius Ptolemy it became clear were not always correct. Likewise the works of the 2nd century Roman physician, surgeon, and philosopher Galen of Pergamon in medicine were found to not always match everyday observations. As the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation clashed the Northern Renaissance showed a decisive shift in focus away from Aristotelean natural philosophy to chemistry and the biological sciences (botany, anatomy, and medicine). The willingness to question previously held truths and search for new answers resulted in a period of major scientific advancements.Some historians view this as a "scientific revolution" heralding the beginning of the modern age. Others simply view it as an acceleration of a continuous process stretching from the ancient world to the present day. Significant scientific advances were made during this time by Galileo Galilei, Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. Copernicus in “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium”, which translates to “On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres”, posited that the Earth moved around the Sun. “De humani corporis fabrica”, which translates to “On the Workings of the Human Body” by Andreas Vesalius, gave a new confidence to the role of dissection, observation, and the mechanistic view of anatomy.

Another important development was in the process for discovery, the scientific method. The scientific method focused on empirical evidence and the importance of mathematics. It discarded Aristotelian science. Early and influential proponents of these ideas included Copernicus, Galileo, and Francis Bacon. The new scientific method led to great contributions in the fields of astronomy, physics, biology, and anatomy. During the Renaissance every continent on the globe was visited except the south polar continent now known as Antarctica. In a period extending from 1450 to 1650 these continents were by and large mapped by Europeans. This development was depicted in the large world map “Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula” made by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu in 1648 to commemorate the Peace of Westphalia.

Another important development was in the process for discovery, the scientific method. The scientific method focused on empirical evidence and the importance of mathematics. It discarded Aristotelian science. Early and influential proponents of these ideas included Copernicus, Galileo, and Francis Bacon. The new scientific method led to great contributions in the fields of astronomy, physics, biology, and anatomy. During the Renaissance every continent on the globe was visited except the south polar continent now known as Antarctica. In a period extending from 1450 to 1650 these continents were by and large mapped by Europeans. This development was depicted in the large world map “Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula” made by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu in 1648 to commemorate the Peace of Westphalia.In 1492 Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain seeking a direct route to India of the Delhi Sultanate. He accidentally stumbled upon the Americas, but believed he had reached the East Indies. In 1606 the Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon sailed from the East Indies in the VOC ship Duyfken and landed in Australia. He charted about 180 miles (300 km) of the west coast of Cape York Peninsula in Queensland. More than thirty Dutch expeditions followed mapping sections of the north, west and south coasts. In 1642 to 1643 Abel Tasman circumnavigated the continent proving that it was not joined to the imagined south polar continent.

By 1650 Dutch cartographers had mapped most of the coastline of the Australian continent except the east coast. The Dutch named Australia “New Holland”. The east coast of Australia was eventually charted in 1770 by Captain Cook. The long-imagined south polar continent was eventually sighted in 1820. Throughout the Renaissance it had been known as Terra Australis, or “Australia” for short. However, afterthat name was transferred to New Holland in the nineteenth century, the new name of “Antarctica” was bestowed on the south polar continent.

From this energetic and evolving society emerged a common, unifying musical language. Particularly notable was the polyphonic style of the Franco-Flemish school. The development of printing made the distribution of music possible on a wide scale. Demand for music as entertainment and as an activity for educated amateurs increased with the emergence of a bourgeois class. The era witnessed the widespread dissemination of chansons, motets, and masses throughout Europe. This coincided with the unification of polyphonic practice into the fluid style that culminated in the second half of the sixteenth century. This is best typified in the work of composers such as Palestrina, Lassus, Victoria and William Byrd.

From this energetic and evolving society emerged a common, unifying musical language. Particularly notable was the polyphonic style of the Franco-Flemish school. The development of printing made the distribution of music possible on a wide scale. Demand for music as entertainment and as an activity for educated amateurs increased with the emergence of a bourgeois class. The era witnessed the widespread dissemination of chansons, motets, and masses throughout Europe. This coincided with the unification of polyphonic practice into the fluid style that culminated in the second half of the sixteenth century. This is best typified in the work of composers such as Palestrina, Lassus, Victoria and William Byrd.The new ideals of humanism were of course more secular in some aspects than religious. Nonetheless these ideals developed against a Christian backdrop, particularly in the Northern Renaissance. Much if not most of the new art was commissioned by or in dedication to the Church. However the Renaissance had a profound effect on contemporary theology. This was particularly so in the way people perceived the relationship between man and God. Many of the periods foremost theologians were followers of the humanist method. They included Erasmus, Zwingli, Thomas More, Martin Luther, and John Calvin.

The Renaissance began in times of religious turmoil. The late Middle Ages was a period of political intrigue surrounding the Papacy. This turmoil eventually culminated in the Western Schism. Three men simultaneously claimed to be true Bishop of Rome. The schism was resolved by the Council of Constance in 1414. However a resulting reform movement known as “Conciliarism” sought to limit the power of the pope. The papacy eventually emerged supreme in ecclesiastical matters as a result of the Fifth Council of the Lateran in 1511. Nonetheless it was dogged by continued accusations of corruption, most famously in the person of Pope Alexander VI. Alexander VI was accused variously of simony, nepotism and fathering four children while a cardinal. The four children were married off, presumably to political allies in the aim of consolidating power, influence, and wealth.

Churchmen such as Erasmus and Luther proposed reform to the Church, often based on humanist textual criticism of the New Testament. In October 1517 Luther published the 95 Theses challenging papal authority and criticizing its perceived corruption. His criticism was especially focused on the sale of indulgences. The 95 Theses led to the Reformation. This was a clear break with the Roman Catholic Church that previously claimed hegemony in Western Europe. Humanism and the Renaissance played a direct role in sparking the Reformation. They also played a significant role in many other contemporaneous religious debates and conflicts.

Muntinous troops under the leadership of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V sacked Rome in 1527. Pope Paul III came to the papal throne from 1534 to 1549. There were grave uncertainties prevalent in the Catholic Church at this time following the Protestant Reformation. Nicolaus Copernicus dedicated De “revolutionibus orbium coelestium”, which translates to “On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres”, to Paul III. Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had already commissioned paintings by Titian, Michelangelo, and Raphael, as well as an important collection of drawings. Afterwards he commissioned the masterpiece of Giulio Clovio, the “Farnese Hours” in 1546, arguably the marking the end of the Italian Renaissance of illuminated manuscripts.

By the 15th century, writers, artists, and architects in Italy were well aware of the transformations that were taking place. Phrases such as modi antichi (“in the antique manner”) or alle romana et alla antica (“in the manner of the Romans and the ancients) to describe their work. In the 1330s Petrarch referred to pre-Christian times as antiqua (“ancient”) and to the Christian period as nova (“new”). From Petrarchs Italian perspective, this new period was an age of national decline, and included his own time. Leonardo Bruni was the first to use tripartite periodization in his “History of the Florentine People”. Brunis first two periods were based on those of Petrarch. However he added a third period because he believed that Italy was no longer in a state of decline. Flavio Biondo used a similar framework in “Decades of History from the Deterioration of the Roman Empire”, which was written from 1439 to 1453.

Humanist historians argued that contemporary scholarship restored direct links to the classical period. Thus they argued that they were bypassing the Medieval period, which they then named for the first time the "Middle Ages". The term first appears in Latin in 1469 as “media tempestas”, or “middle times”. However the term rinascita, or “rebirth”, first appeared earlier. The term in its broadest sense was used in Giorgio Vasaris “Lives of the Artists”, written in 1550. Vasari divides the age into three phases. The first phase contains Cimabue, Giotto, and Arnolfo di Cambio. The second phase contains the artists Masaccio, Brunelleschi, and Donatello. The third stage centers on Leonardo da Vinci and culminates with Michelangelo. According to Vasari it was not just the growing awareness of classical antiquity that drove this development. The development was also spurred on by the growing desire to study and imitate nature.

In the 15th century the Renaissance spread rapidly from its birthplace in Florence to the rest of Italy and soon to the rest of Europe. The invention of the printing press by German printer Johannes Gutenberg allowed the rapid transmission of these new ideas. As it spread its ideas diversified and changed, adapting to local culture. In the 20th century scholars began to break the Renaissance into regional and national movements. In England the 16th century marked the beginning of the English Renaissance. Leading the transition into the Renaissance were the work of writers William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spenser, Sir Thomas More, Francis Bacon, and Sir Philip Sidney. The transition also was effected by great artists and architects such as Inigo Jones who introduced Italianate architecture to England. Château de Chambord built from 1519 to 1547 is one of the most prominent and famous examples of Renaissance architecture. Composers such as Thomas Tallis, John Taverner, and William Byrd participated in a Renaissance of music.

The word "Renaissance" is borrowed from the French language. In French the term means "re-birth". The term was first used in the 18th century. It was later popularized by French historian Jules Michelet in his 1855 work, “Histoire de France” or in English, the “History of France. In 1495 the Italian Renaissance arrived in France, imported by King Charles VIII after his invasion of Italy. A factor that promoted the spread of secularism was the inability of the Church to offer assistance against the Black Death. Francis I built ornate palaces at great expense and imported Italian art and artists, including Leonardo da Vinci. Embracing the spirit of the Renaissance were writers such as François Rabelais, Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay and Michel de Montaigne. Likewise swept up were painters such as Jean Clouet, and musicians such as Jean Mouton.

In 1533 a fourteen-year-old Caterina de Medici married Henry II of France. Caterina had been born in Florence to Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbino and Madeleine de la Tour dAuvergne. Henry II was the second son of King Francis I and Queen Claude. Caterina became both famous and infamous for her role in Frances religious wars. However she also made a direct contribution in bringing arts, sciences and music to the French court from her native Florence. This included a performing art form which was the origin of ballet. In the second half of the 15th century the Renaissance spirit spread to Germany and the Low Countries. There the development of the printing press around 1450 and Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer predated the influence from Italy. In the early Protestant areas of the country humanism became closely linked to the turmoil of the Protestant Reformation. The art and writing of the German Renaissance frequently reflected the dispute between the Roman Catholics and the Protestants.

However in Germany the Gothic style and medieval scholastic philosophy remained entrenched until the turn of the 16th century. Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg who ruled from 1493 to 1519 was the first truly Renaissance monarch of the Holy Roman Empire. After Italy Hungary was the first European country where the Renaissance appeared. The Renaissance style came directly from Italy during the Quattrocento to Hungary first in the Central European region. This was consequence of the development of early Hungarian-Italian relationships. These relationships were not only in dynastic connections, but also in cultural, humanistic and commercial relations. These ties had been growing in strength from the 14th century.

The relationship between Hungarian and Italian Gothic styles was a second reason for the advancement of Renaissance ideals into Hungary. These architectural styles avoided the exaggerated breakthrough of walls, preferring instead clean and light structures. Large-scale building schemes provided ample and long term work for the artists. Examples would include the building of the Friss (New) Castle in Buda, as well as the castles of Visegrád, Tata and Várpalota. In Sigismunds court there were patrons such as Pipo Spano, a descendant of the Scolari family of Florence. It was Spano who invited Manetto Ammanatini and Masolino da Pannicale to Hungary.

The new Italian trend combined with existing national traditions to create a particular local Renaissance art. Acceptance of Renaissance art was furthered by the continuous arrival of humanist thought in the country. Many young Hungarians studying at Italian universities came closer to the Florentine humanist center. It was then natural that a direct connection with Florence evolved. The growing number of Italian traders moving to Hungary helped this process. This was particularly evident in Buda, New thoughts were carried by the humanist prelates. Among those were Vitéz János, archbishop of Esztergom, one of the founders of Hungarian humanism. During the long reign of emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg the Royal Castle of Buda became probably the largest Gothic palace of the late Middle Ages. King Matthias Corvinus who reigned from 1458 to 1490 rebuilt the palace in early Renaissance style and further expanded it.

<" alt="Venise Italie Vénétie vue des airs palais économies picturaux cathédrale canaux îles ÉNORME" width="52" height="52" >

Buy now.

Pay later.

Earn rewards

Representative APR: 29.9% (variable)

Credit subject to status. Terms apply.

Missed payments may affect your credit score

FrasersPlus

Available Products

SIMILAR ITEMS

- Venise Italie Vénétie vue des airs palais picturaux cathédrale canaux îles ÉNORME

- RENAULT 402029333R

- Chevrolet K5 Blazer Silverado 1984 blanc levé tout terrain 48 COUNT CASE 1:64

- 4 x Sonde lambda DELPHI pour AUDI, SEAT, SKODA, VW A1, A3, A3 8P, A3

- Daiwa Köder Rolle 22 Zillion Tw HD 1000XH

- Lunettes de vue Cartier CT0005O couleur 010 noir taille 55 neuves dernière

- Lunettes de soleil Chopard gris acétate

- 2021-22 Merlin Collection Chrome UCL Rouge Réfracteur /10 Luka Sucic Rookie Auto RC

- Dell MXG610S 32Gb Faser Kanal Schalter Modul Für MX7000 Brandneu

- KARL LAGERFIELD POCHETTE 10 PHOTOS CHANEL HAUTE COUTURE AUTOMNE HIVER 2008 /9